Having broken my knee cap, I’ve spent a lot of time surfing about what to expect and do so I thought it might be useful to write up my experience as a guide to others, though I wouldn’t wish a broken knee cap on my worst enemy. I have generally been very impressed with the quality of care I received at the Whittington Hospital, though one criticism I would have is that I wasn’t given any sort of leaflet on what to do or what to expect at any stage (except by the physiotherapists, who clearly understand that patients do not have perfect memory). Even if medical professionals give you all the right advice, which they probably don’t because they are busy and fallible, I don’t think you can really expect a patient, who at various times is shocked, drugged, tired, depressed or scared to remember everything that they are told. So I would have found it helpful to have something in writing for clarity.

I hope this might help others, though it does of course come with the caveats that it is only based on one person’s experiences, different cases will be different and I am not a medical professional.

Now, six weeks after my operation, and the day after I have been given the all clear to put my weight through the affected leg, seems a good time to write this, as I move to the next phase.

Day 0 (Friday 8 December) hitting the pavement can break a bone

Breaking a knee cap is painful. Falling over as an adult is generally a shock and I always want to get straight up but I didn’t feel I could. One passerby told me I was making a fuss. Another, who claimed to be a first aider (though she must have done her course a long time ago) told me to try standing up. I thought I would try standing up after a few minutes when the shock had worn off a bit but I really didn’t want to move. I think my lycra cycling tights probably masked the swelling. I remember yelping as I hopped up the steps into the ambulance. I felt slightly sick when I took my lycra off lying on a stretcher in the ambulance and the knee seemed to pop up a few centimetres. Even then, I thought taking me to hospital for an x-ray was precautionary and was quite surprised to be told that my knee cap was in 3 pieces. So I would draw the lesson that if it really hurts (and I am sure there are far more painful things) it’s worth getting it checked and that if you have the misfortune to have a hard blow to your knee cap, it may well break.

So I went from being surprised that I had a broken bone to being told that I would have an operation the following day to signing a consent form about all the things that might possibly go wrong in a few minutes. A few hours later, I was wheeled on a trolley into a ward for my first overnight stay in hospital since I was born. Apart from being really bored until my family visited later on, I don’t think much of note happened until it was time to go to sleep. The night nurse then told me that I shouldn’t hobble to go to the toilet as I might make the swelling worse and they wouldn’t be able to operate if my knee was too swollen. I still don’t know if this was true but it really worried me, particularly as I had read by then about the importance of having a broken knee cap fixed into position quickly.

So it was not only my first night in hospital but my first night of weeing into a bottle with four other patients in close proximity. My first attempt was totally unproductive after a long wait but I soon got into the swing of things

Day 1 (Saturday 9 December) Patella ORIF

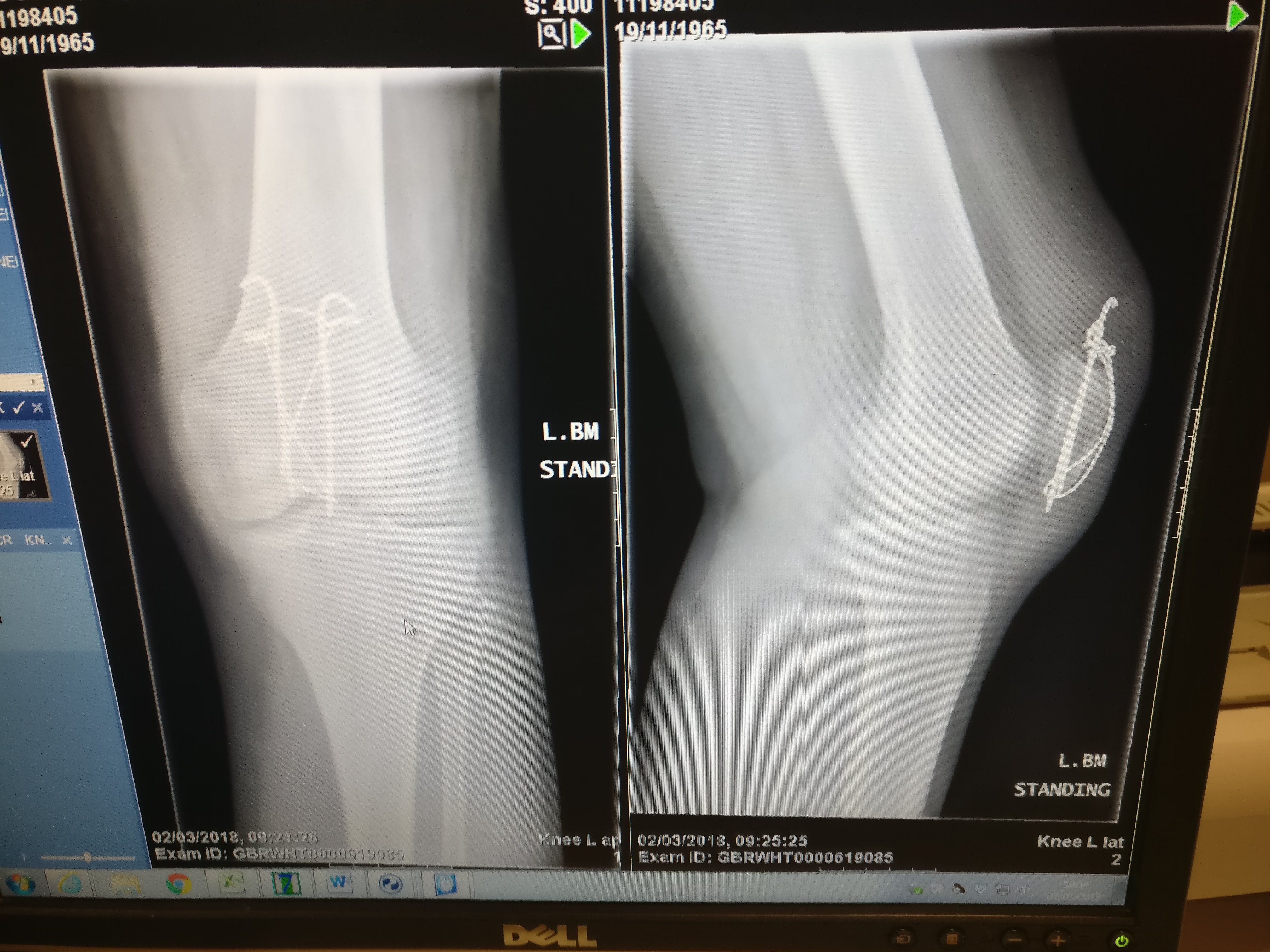

Most contacts with professionals involve learning a new language. I just about knew that doctors call a knee cap a patella though I still have to check that it’s not a patellar. However, ORIF was an unexpected new acquaintance. ORIF means Open Reduction Internal Fixation, so the surgeon cuts your knee open and then internally fixes the broken bits together. If you are lucky a simple fracture might not need this, but my knee cap was split in two with a significant gap and one of the halves had a further fracture. The surgeon told me that when they put the big pieces together the little piece came into line. In my case the fixation was two stainless steel pins to hold the knee cap in place, and then some wire wrapped around it to stop the bone slipping on the pins.

I woke up a bit confused after 2 hours under general anaesthetic to find that my affected leg was totally wrapped in bandages and it was only a few hours later that I realised there was also a plaster cast on the back of the leg, from half way up my thigh to covering most of my foot so that my ankle as well as my knee were immobilised. In fact the plaster went so far up my thigh that I had to sit forward in a chair with several cushions behind me to stop the top of the plaster sitting uncomfortably underneath me.

Day 2 (Sunday 10 December) discharge him before he turns into a heroin addict

One of my first memories of the morning was being told to take a diamorphine tablet. I was quite surprised when google told me it was heroin. I was slightly disappointed not to be discharged with any, though that’s probably a good thing since google also told me how highly addictive it is. I was discharged with 3 different pain killers but I barely took any after the first night back home.

I also awoke to snow, which was even more unwelcome when I eventually left hospital in the dark of night.

I was visited by two physiotherapists in the middle of the morning who said they would teach me how to walk again. This seemed a bit over the top, since I had last walked about 36 hours previously. I realised what they meant when they started me off on a zimmerframe before moving me on to crutches. It was less than 24 hours since my ORIF and hobbling a few steps on the zimmerframe was hard work. I was really grateful that they taught me to go up and down stairs and spent the next few days at home carrying their leaflet around with me. I eventually learnt that going up stairs means leading with your good leg, and that your bad leg goes down first, with the crutches staying with the bad leg. Simple, but it does take some learning, and painful and confusing when you get it wrong.

This has turned into a much longer post than expected, so I will continue in another part. For the next few weeks, I found this useful as a rough guide to my recovery protocol though I inevitably didn’t follow it exactly